Widening inequalities in healthy life expectancy mean the majority of Britons will develop disabilities before state pension age that could leave them relying on working age benefits for support, a hard-hitting report headed by Michael Marmot has found.

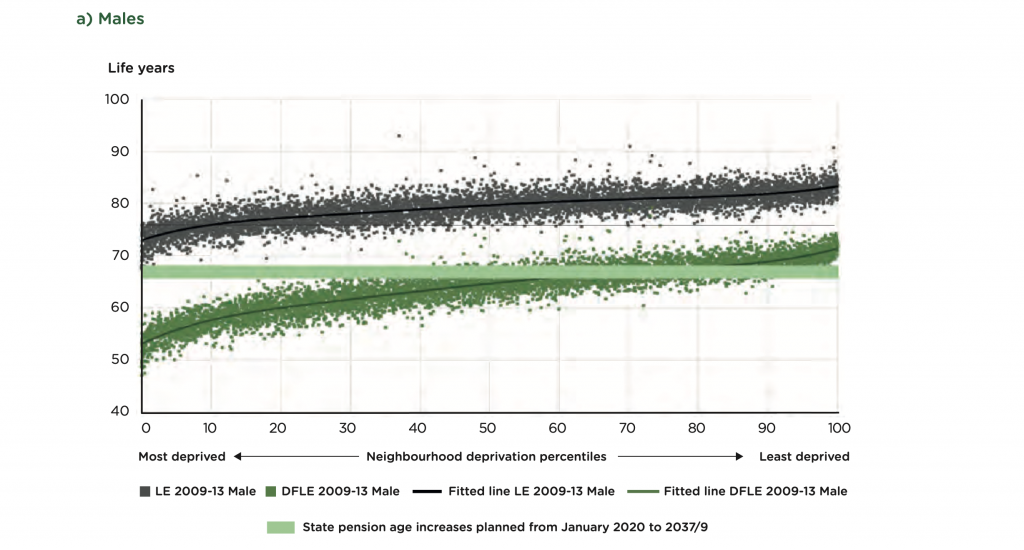

The report – Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On, by the Institute for Heath Equity – has found that only people in the least deprived 20 to 30 per cent of areas in the UK can expect to receive their state pension before they can expect to develop a disability.

The remaining 70 to 80 per cent of neighbourhoods can expect to enter retirement with health conditions, based on the current increases in state pension age.

The poorest neighbourhoods in England have a disability-free life expectancy of just 50, compared to over 74 years for the wealthiest, according to the report.

The table above shows male life expectancy (black dots) and disability-free life expectancy (green dots) for the most to least deprived neighbourhoods in the UK. The light green bar represents the projected increases in state pension age. The proportion of females reaching state pension age without disability is slightly lower.

Since 1981 male life expectancy has increased more quickly than female life expectancy, especially during the 1990s, the report shows. As a result, the gap in life expectancy at birth between males and females narrowed from 6 years in 1981 to 3.6 years by 2012, where it has more or less remained ever since.

In England, the difference in life expectancy at birth between the least and most deprived deciles was 9.5 years for males and 7.7 years for females in 2016-18. In 2010-12, the corresponding differences were smaller – 9.1 and 6.8 years, respectively. Life expectancy at birth for males living in the most deprived areas in England was 73.9 years, compared with 83.4 years in the least deprived areas; the corresponding figures for females were 78.7 and 86.3 years in 2016-18. Males in the five least deprived deciles, approximately 50 percent of the male population, could expect to live beyond the age of 80 years, while those in the five most deprived deciles could not. Females in the most deprived decile could also not expect to live more than 80 years, while those in the two least deprived deciles could expect to live beyond 85 years.

Report lead author Michael Marmot says: “England is faltering. From the beginning of the 20th century, England experienced continuous improvements in life expectancy but from 2011 these improvements slowed dramatically, almost grinding to a halt. For part of the decade 2010-2020 life expectancy actually fell in the most deprived communities outside London for women and in some regions for men. For men and women everywhere the time spent in poor health is increasing.

“Globally, actions to address inequalities have moved on since 2010. We are reporting in the era of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, or SDGs. At least 11 of the 17 SDGs can be seen as key social determinants of health. The twin problems of social inequalities and climate change have to be tackled at the same time. Addressing each is vital to creating a society that is just, and sustainable for the current and future generations. New Zealand has shown the way a government can reorder national policies. The government there has put wellbeing, not growth, at the heart of its economic policy: enabling people to have the capabilities they need to lead lives of purpose, balance and meaning.”

Club Vita engagement lead Mark Sharkey says: “For society, the challenge of linking state pension age to life expectancy: For many decades life expectancy rose steadily rose without any equivalent increase in state pension age. A need to “balance the books” led to legislation to link future rises in state pension age to changes in life expectancy. However, what happens when the life expectancy stalls or even decreases? Do we continue to increase state pension age or leave it untouched? This decision is harder when we have widening inequalities in life expectancy, as those most reliant on the state pension are liable to also be the shortest lived. Without addressing health inequalities at source, is there a risk that the attempt to plug a leak in state pension funding may be thwarted by the increased welfare payments made to the most disadvantaged during the period when state pensions have been deferred.”

“For DB pension schemes, the flaw of relying on headline trends: Those responsible for scheme funding need to be alert to the risk of using average increases in life expectancy for funding projections. This is what many pension schemes are doing by virtue of adopting an unadjusted version of the “CMI model”. For most schemes the lion’s share of scheme liabilities (and therefore risk) lies with the most affluent individuals. It is these individual who have been most resilient to the recent stalling in national life expectancy. Failing to reflect the socioeconomic landscape of the scheme membership risks underestimating the cost of providing benefits.”