There is clear political and regulatory momentum to encourage DC schemes to broaden their investment remit and commit more money into private markets.

A recent roundtable, held by Natixis Investment Management in partnership with Corporate Adviser, industry professionals from across the DC landscape, including trustees, consultants, providers, regulators and those working for platforms, discussed the potential benefits of these illiquid investments, as well as current barriers to wider adoption.

DOWNLOAD THE ROUND TABLE SUPPLEMENT HERE

One key issue was the potential performance boost illiquids can offer DC defaults as part of a diversified investment strategy. Natixis IM Solutions director Jochem Tielkemeijer said there are a number of reasons DC schemes might want to consider allocations to private markets. These include diversification, lower volatility, inflation hedging and ESG objectives — as well as enhanced returns.

However, given the higher cost of investing much of the drive to include illiquids is likely to be framed around the performance question — and whether higher asset allocations to private markets can deliver better member outcomes.

Tielkemeijer said that while there seemed to be consensus across the investment industry that private markets offer an “illiquidity premium”, there remains debate as to the size and significance of this enhanced return.

Given the lack of clear public data on performance for private assets, which are, by their very nature private, views will “depend on who you are speaking to within the industry” as well as the duration and timing of these investments and the particular asset class, be it venture capital, private equity or private debt, he said.

But Tielkemeijer attempted to quantify what this range of enhanced returns might mean within a DC context, by using data from the Corporate Adviser Pension Average (CAPA) data set, which shows average asset allocations and returns for the default funds of all the major DC master trusts and GPPs operating in the workplace pensions market.

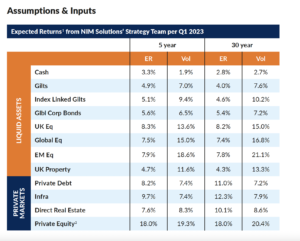

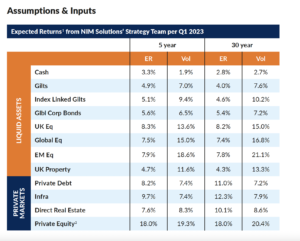

Natixis IM’s future scenario modelling takes into account both macro factors and long-term return assumptions for the major asset classes. These inputs, collated from a range of sources, suggest future returns from private debt, infrastructure, direct real estate and private equity are all likely to outperform expected returns on global equity — and outperform significantly in the case of private equity.

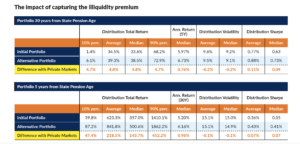

Given these projections, Tielkemeijer modelled how a 10 per cent allocation to illiquids could impact future DC returns on typical default constructions. On the default portfolio for investors in the growth phase (30 years from SPA) this allocation boosts the median annualised return from 5.2 per cent, per annum to 6.16 per cent pa— a difference of 0.96 percentage points.

Tielkemeijer said that while this may look like a modest increase, it has a marked effect on total returns over a 30 year period, with the average total return increasing by 218.5 per cent. Even on the worst-performing default funds (in the bottom 10 per cent performance-wise) a default with a private market allocation should see total returns increase by 47.4 per cent (compared to an allocation without private markets) while the top performing funds should see a 452.2 per cent uplift.

This translates into approximately 20 per cent increase in capital at retirement according to Natixis’s figures graph — or a 42 per cent increase in pension capital with a 20 per cent private markets allocation (see graph below). It also significantly increases the probability that members will be able to outpace inflation.

Natixis IM also modelled returns for defaults five years from retirement. The average boost to annualised returns was broadly similar, although as this was over a shorter timeframe the effect to total returns was more modest.

Private asset allocations were different for different age cohorts. During the growth phase Natixis modelled a larger (6 per cent) weighting to private equity, with smaller allocations to private debt, infrastructure and direct real estate, while the allocation five years to SPA included 5 per cent in private debt and 3 per cent in private equity and just 1 per cent invested in real estate and infrastructure.

While those attending the debate did not disagree that illiquids could boost returns, there was scepticism around some of the assumptions made, particularly the expected returns for private equity which forecast 18 per cent a year going forward, compared to 7.4 per cent for global equity, 7.9 per cent for emerging market equity and 5.6 per cent for global corporate bonds.

Andy Cheseldine a professional trustee with Capital Cranfield said this is unlikely to include the ‘cash drag’, typical on most private market investments, with returns typically not paid out until the sixth or seventh year. This ‘J-curve’ effectively dampens returns he said, and could make the premium above global equity less impressive”, although Natixis head of UK DC strategy and sales Nick Groom said the cash drag impact could be minimised by the fund structure.

Given these figures are net of charges Chesledine suggested a 18 per cent projection for private equity as an “heroic assumption”. But Tielkemeijer countered that even if the returns were several percentage points lower than this, there would still be an overall performance boost.

There were comments that while private markets have delivered strong returns in recent decades. this has been in relatively benign economic conditions where low interest rates have seen increase funds ploughed into this sector.

Shula PR and Policy managing director Darren Philp said he would like to know what kind of economic scenarios might see a reverse of these figures, where global equity outperforms private equity?

He also asked another provocative question. “If this outperformance looks so impressive, why are we proposing just a 10 per cent allocation to private markets?” Although he did not necessarily recommend allocations of 40 per cent plus — given liquidity issues and the overall size of the market — he said making bold performance claims for illiquids could trigger such questions.

Tielkemeijer said that data on the performance of private markets is, by definition more limited, when compared with the raft of information available from publicly listed markets. “This is self reported data, so you have self-selection and also survivorship bias. Assumptions are just that, assumptions and need to be taken with a grain of salt,” he said.

But he said these figures are based on information from leading private market data providers, just as Cambridge Associates, practitioners such as Yale Endowment and a range of academic papers.

The roundtable discussion highlighted one important aspect of performance — the considerable difference in private equity returns between the top and bottom of the market.

Flexstone managing partner Eric Deram said DC schemes need to gain exposure to these higher performing private market investments.

“In private equity the average is not interesting; you need to be first or second quartile to deliver good results.” He pointed out that in a survey of private equity vintages over the past 20 years, around half did not achieve sufficient performance to trigger their performance-related fee. He also questioned whether those pension providers who had achieved investments in private equity without embracing 2 and 20 charges would get access to the best investments. He said even big investors struggled to get access to the very best private asset funds, as they were competing with huge high prestige investors such as the Yale, Harvard and Princeton endowments.

This question of selecting the right investments raised an interesting discussion point for trustees and consultants. In recent years default investment strategies have favoured passive strategies, which trend in line with the market averages rather than trying to pick winners. Would this approach have to change to incorporate private market allocations? And do those working across the DC sector have the necessarily skillsets to do this?

The Investment Association senior policy adviser Imran Razvi said he did not think that this was significantly different to the decisions made around active management. Those attending the debate added that schemes were likely to use fund managers that specialise in this area.

But XPS partner and head of DC Sophia Singleton said one of the reasons private markets weren’t a key part of most DC portfolios was that management charges were expensive — and the DC world remains price driven. She added there was also a reluctance to change investments within defaults as this also incurs additional costs.

Philp agreed with this analysis: “There are certain types of investment that are much easier for people to get their heads around. Often this is a capacity issue as well as a price issue. We know that time can be an issue when it comes to trustee meetings. So the more exotic you go in terms of asset class, the more effort and work you need to put in and this has been a key barrier preventing the wider take up of private market investments in DC.”

Many around the table agreed that when it came to performance there was often a ‘herd’ mentality within the DC sector. Deram pointed out that this isn’t just an aspect of the UK DC sector – it is a trend he’s observed globally with pensions.

Ben Van den Tol, director business development at AMX, which offers LTAFs in the UK said useful lessons can be learned from Australia, where he previously worked. There schemes compete on net returns, he said, marketing themselves direct to members, not just employers. This puts far greater focus on investment performance, rather than price alone.

The focus on price in the UK means schemes have been reluctant to embrace private markets, which add costs and may only drive performance after several years. In Australia he said it was the schemes

that invested heavily in private market 15 years ago that are now delivering the strongest returns, and have subsequently attracted new business as a result. This has driven similar investment strategies among competitors he said. Australian Super giant Hostplus, for example, has nearly 50 per cent of its default allocated to non-listed assets.

Recently Australian regulators have move to take action against under-performing funds. While Van den Tol said this has been effective in removing “deadwood and dross” he warned this may only be an effective strategy over the short-term.

A focus on action against underperforming schemes could result in more of a herd mentality in the long-run, he said, with schemes reluctant to pursue investment strategies that risk short-term underperformance, even if there may be more of an longer-term upside.

While there was considerable focus on the performance impact of illiquids and private market investments, the modelling and analysis undertaken by Natixis showed that this wasn’t the only significant benefit offered to default portfolios.

While private market investments, particularly private equity can be a more volatile asset class than equities or bonds, its inclusion within the multi-asset portfolio can reduce the distribution volatility of the whole portfolio according to Natixis analysis.

Tielkemeijer pointed out that the volatility of default portfolios, both during the growth phase and five years to SPA, are lower with these assets. This is in part due to increased diversification and relatively low correlation on returns from these different asset classes.

Deram said that all various data points relating to performance suggests that it could prove beneficial for DC portfolios, despite the higher management and investment costs.

Despite the increase in private market investments in recent years he said that there is still substantial opportunity in this asset class. Rather than focus on the minutia of this data he said it was important for scheme managers and investment specialist to look at the bigger picture.

“If you ask me why you should invest in private markets, my main answer is because the world is essentially private.

“Around 80 per cent of the world’s companies are privately owned, this includes some of the very biggest companies to start up enterprises that will be the engines for creating future wealth.

“You now have more private companies than public companies so it is much easier to diversify your portfolios. I went to my first private equity conference in the 1990s and one of the issues debated was whether there was too much money in private equity. That was close to 30 years ago and the industry is 50 times bigger today. My message is there is still substantial opportunity in these diverse markets.”