SPONSORED CONTENT

Future generations of older people are more likely to live in a rented home than they are today. So what does this mean for their retirement plans?

Are many estimates about retirement adequacy understating the severity of the problem?

It’s not a nice thought. But, if true, it’s one that the pension industry and society as a whole should face into.

We know from various studies that many people are set for a retirement financially less comfortable than they would like, or expect.

For example, government figures released in March 2023 projected that around half of working-age people will have a pension income below a Moderate Standard (using the PLSA’s Retirement Living Standards).

And more than a tenth of working-age people are projected to have a pension income that falls below a Minimum Standard.

Unfortunately, the real problem could be worse than this.

Why? Because the government’s model assumes that home ownership will continue at similar levels in retirement to existing levels (just under 80%).

The PLSA’s Retirement Living Standards are extremely useful for helping people to picture the lifestyle they want when they retire, and understand what it might cost.

For now, they understandably assume that people will be mortgage- and rent-free in retirement, because this is still what most of the population close to retirement will achieve in the next few years.

Yet future generations of older people are more likely to live in a rented home than they are today. In fact, those aged over-65 are one of the fastest-growing tenant groups.

Rental trends

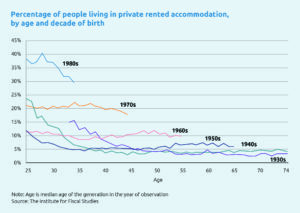

For those born in the 1930s and 1940s, less than 5% of the population were private renters in their late 60s and early 70s (see Figure 1).

Among those born in the 1950s, only 6% were private renters in their mid-60s. These are the rates of private renting seen among retirees now.

For those born in the 1960s, the fraction who are private renters has been stuck at 10% for around three decades and shows no clear signs of falling. If this cohort continues to rent past retirement, we could see a seismic shift in the demographics of private renting.

Potential rates of private renting among those approaching retirement could be even greater for younger generations.

Take those born in the 1970s. About 18% of them were in private rented accommodation by the time they reached their mid-40s. So it would not be surprising if rates remained around 15% when they enter retirement.

Figure 1: More people are living in private rented accommodation

What about inheritance?

These trends mean that a growing fraction of the population will have to save for a retirement that includes paying rent each month.

State support would be available to some people, in the form of Housing Benefit, but this is only available to those on low incomes and may not cover the full cost of private renting.

Inheritance might mitigate this problem, but not necessarily.

Of those born in the 1940s, just under a third received an inheritance. Meanwhile, over two-thirds of those born in the 1970s have received, or expect to receive, an inheritance.

However, relatively few people will inherit enough to purchase a home outright.

Additionally, those who are most likely to receive significant inheritances are likely to be richer themselves, and therefore likely to already be homeowners. So the people who would most materially benefit from receiving an inheritance are less likely to inherit very much, if anything.

Care costs

That’s not all. Most estimates of retirement adequacy also do not account for the potential costs of requiring social care.

Healthy life is around 63 years for men, and around 64 for women, according to the ONS.

Yet life expectancy is 79 years for men and 83 years for women. This means that many people could spend a lot of their retirement in ill health, potentially needing to access costly care.

Of course, these problems reflect larger structural and economical challenges within the UK, so I’m not suggesting the pension industry alone can solve them. But we can help to move the conversation in the right direction.

As we know, financial preparedness is about more than just pensions and savings. And in future it will become even more important that, as an industry, we support people to prepare for retirement holistically by considering their assets, housing costs and potential care costs.

Only then, will we have a realistic sense of the support people need when planning for retirement.