[SPONSORED CONTENT]

In wealthy countries, 80% of the gender employment gap stems from some women leaving work after the birth of their first child.

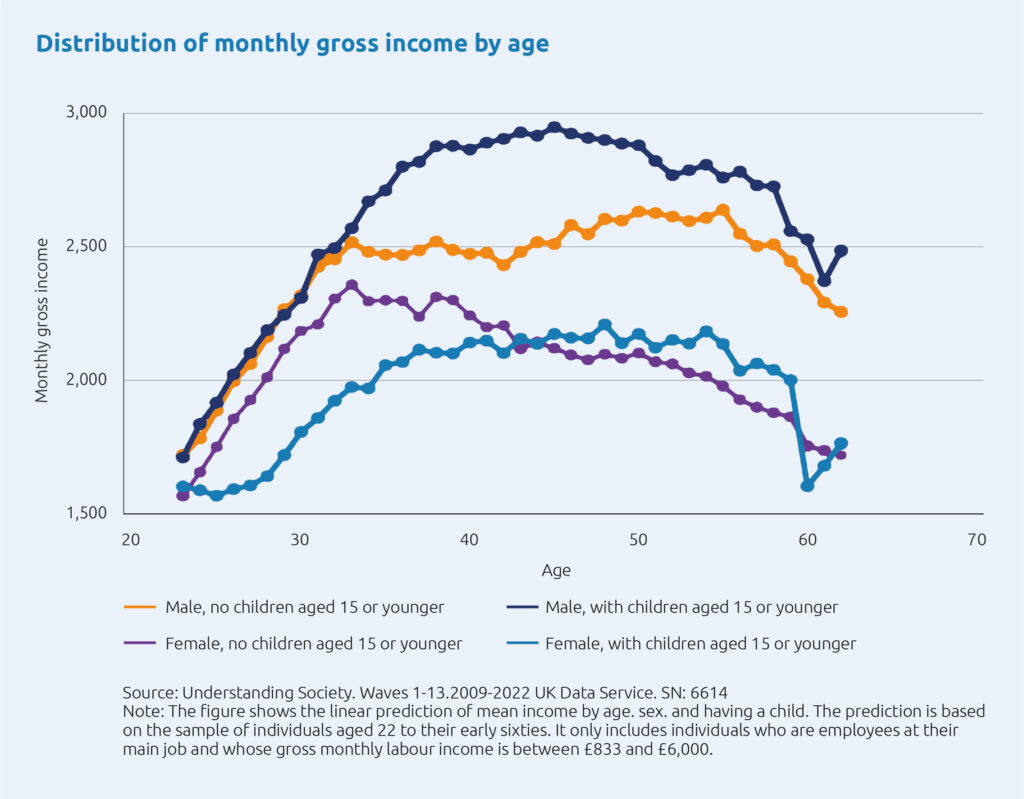

Men with young children generally earn more than other men. This is true for men in their mid-thirties up to men in their early sixties.

Meanwhile, for women in their twenties and thirties, having children is associated with a much lower income than other women. Older women with young children, though, tend to have higher incomes than other women (see Figure 1).

How should we interpret this?

Figure 1: For a lot of women, having children is associated with a lower income

International challenge

In a nutshell: motherhood appears to significantly affect women’s participation in the workplace.

A study by academics from Princeton University and The London School of Economics and Political Science defines this drop in a woman’s likely employment after the birth of her first child as the “motherhood penalty”.

The study collected data from 134 countries (95% of the world’s population). It found that, on average, 24% of women leave the workforce within a year of having their first child. Ten years later, 15% are still missing from it.

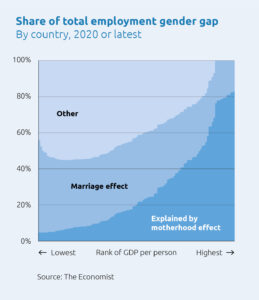

In fact, in wealthy countries, 80% of the disparity in labour force participation between women and men can be explained by women exiting the workforce after the birth of their first child (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: In wealthy countries, 80% of the gender employment gap can be explained by motherhood

Closing the gap

Arguably many factors contribute to this problem. But one factor is heavily involved, according to Claudia Goldin, a Harvard economist who was awarded the 2023 Nobel prize in economics for her research into gender inequality in the labour market.

Many employers still reward employees disproportionately for putting in extra hours – often within fairly rigid timeframes. This often disadvantages people with caring responsibilities, which includes a lot of mums.

Women with young children often seek flexibility in their work. But, right now, flexibility costs many workers, particularly women, too much – both in pay and career prospects.

Conversely, this often causes many fathers to “lean in” to their careers – taking little time off after the birth of children, and logging long hours at work.

This often drives the ‘couple inequality’ and income divergence seen among a lot of heterosexual couples after children are born.

To a large extent, Goldin’s research suggests, the size of an industry’s gender employment and pay gap reflects not discrimination, but how its businesses organise their working patterns.

Cheaper flexibility

So how are we to fix this problem?

The solution, according to Goldin, lies in employers providing ‘cheap flexibility’. This means women (and anyone else, for that matter) being able to take care of children, or other loved ones, without paying a heavy professional cost.

Flexible work is an intrinsic part of good work. It enables not just parents, but carers, disabled people, and those moving from benefits to enter and remain in the workforce.

This is why Standard Life supports the government’s new flexible working regulations, which came into effect on 6 April 2024.

This gives employees the right to request flexible working arrangements from day one of employment. Previously, workers needed to have been employed for at least 26 weeks before making such a request.

Next steps

We recognise that employers must take decisions that are right for their business. So we have called for action from government and employers that does not put heavy burdens on the business community.

This is why we are calling for the government to:

- Set out guidelines to help employers understand and explore alternatives if they are unable to accommodate a flexible working request.

- Amend legislation to reduce the number of reasons for an employer to reject flexible working arrangements, once data on formal flexible working requests has been collected.

- Make statutory changes to compel employers with more than 250 employees to publish the number and percentage of people that had a formal flexible working request declined.

These measures will benefit many different groups of people, who may otherwise find their participation in the workplace compromised. In turn, we hope this will contribute to a more equal, productive and happy society.