The US is likely to remain an important source of global equity returns in future, despite current concerns about concentration risks and a potential AI bubble.

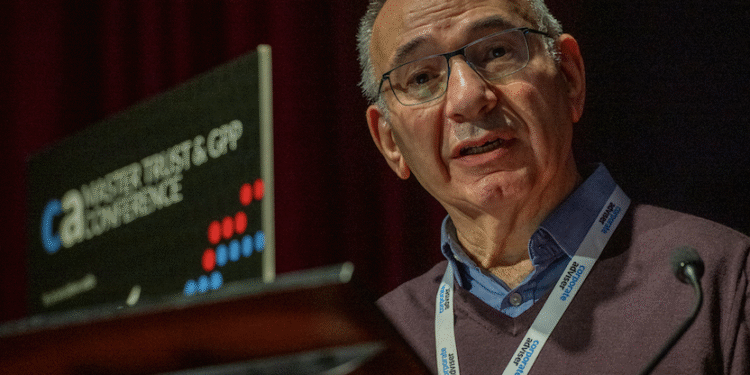

This was one of the key takeaways from a presentation at Corporate Adviser’s Master Trust and GPP Conference by Elroy Dimson, Professor of Finance at the Cambridge Judge Business School — and co-founder and chairman of the Centre for Endowment Asset Management.

Drawing on his work with major endowments and sovereign wealth funds, Dimson brought a long-term, evidence-based perspective on the performance of different asset classes and stock markets, highlighting the “remarkable outperformance” of US equities over the past century.

As Dimson pointed out, those investing in US equities have seen annualised real returns of 6.6 per cent since 1900, compared to just 4.3 per cent for global equities excluding the US. (All returns are in dollars.)

For someone investing $1 in global equities (ex US), this would have produced a return of $194 over this 124-year period. In comparison, a $1 investment into US equities would now be worth $2,911.

Dimson’s statistical analysis showed that while there are concerns about concentration in the US market — particularly relating to a small number of very large tech stocks — the market is not as concentrated as some other countries. “The US is not unusual in this regard,” he said.

Where it is unusual, he noted, is in the extent to which the largest stocks have “punched well above their weight in performance terms”. Taking a strategic bet against this concentration would not have delivered positive results historically, he said.

Dimson acknowledged that some active managers are looking to diversify away from the US and this narrow range of stocks. But he said he “would not lose sleep being exposed to US markets” at present. Some active managers are taking significant positions against the US market, he noted, but cautioned against the risks of market timing — particularly as the US now accounts for more than half of global market capitalisation.

Dimson also examined the long-term performance of private market assets, particularly in light of DC schemes looking to build substantial exposure to these areas. Data from the Cambridge Associates Buyout Index — which compiles performance data on private markets — shows that from 1983 to 2024, private equity delivered an annualised return of 10.4 per cent. Dimson said that while the S&P 500 delivered 8.5 per cent over this period and the Russell 2000 6.1 per cent, these figures contain an element of “volatility smoothing”.

A better comparison might be to smaller company indices, with the Fama–French Small Value Index delivering 9.7 per cent, he said.

Dimson pointed out that private equity remains an expensive asset class suited only to investors who can afford to take a multi-decade or even multi-century view. He added that there are persistent issues around higher costs, transparency, volatility and survivorship bias.

Dimson also discussed the relative performance of other assets, including bonds, cash and gold. He pointed out that gold has not proved to be a good inflation hedge. International diversification is important, he said, across both geographies and asset classes.

Looking towards the inclusion of private markets in DC, Dimson said that schemes need to be realistic about future outcomes, particularly with the tailwinds of falling interest rates and cheap leverage no longer present.

He pointed out that governance, diversification and tight control of costs will continue to be critical, and that some DC schemes may find it difficult to import endowment-style strategies without the same time horizon, risk tolerance and organisational structures.