What do you get if you cross an investment consultancy with a covenant specialist? An organisation that can better understand the risks facing a pension scheme – and how it can invest most efficiently in order to meet those risks. That is synergy being claimed by Cardano and Lincoln Pensions since the two organisations came together last October. John Greenwood talks to Cardano UK CEO Kerrin Rosenberg and Lincoln Pensions CEO Darren Redmayne

Darren Redmayne (left) and Kerrin RosenbergCardano is best known as a force in DB investment consulting, but it is involved in a number of initiatives designed to improve understanding of investment risk for the benefit of end investors, projects that see it developing a new proposition for the UK DC market that challenges industry norms around equities, targeting improvements in performance transparency and engaging in new ways to communicate and educate on risk.

For Rosenberg, the acquisition of Lincoln has given the firm a deeper understanding of what risk means for organisations, in a way that goes beyond the pension scheme, that gives it a better platform for protecting members’ benefits.

Rosenberg says: “The two big planks of safety are the sponsor and the pension scheme investments and it is a glaring gap in the system that you have two separate conversations. If you put them both together you can have a much richer conversation.”

By bringing the sponsor’s own macro and business-specific factors into the overall scenario planning, a richer risk modeling process can be achieved says Redmayne.

“For example, you might find that an inflation scenario is really good for the sponsoring employer, so you don’t need as much hedge against inflation as you might otherwise expect. So that could mean you can actually take more risk, or more exposure to the inflation scenario, while being really cautious about interest rates because that is a thing that would really hit the employer. And we can do the same in reverse and make sure we haven’t got any unintended correlations in the assets strategy,” says Redmayne.

Other investment consultants might argue they can and do take precisely these factors into account when they use the services of covenant specialists, including Lincoln. For Rosenberg and Redmayne the added level of insight comes from the fact of having both sets of expertise operating side by side within the same organisation.

Redmayne says: “Cardano faces off against the big three consultancy firms and Lincoln faces off against the big four accountancy firms, but put us together and there is nobody doing what we are doing together.”

So does this leave them less in the regulator’s line of fire than others when it comes to the asset management market study, and the conflicts of interest charges leveled at investment consultants?

Rosenberg says: “Cardano along with other firms has two weeks to give our thoughts to the FCA on this.

“On conflicts, we think integrated risk management is a triangle made up of covenants, investment and funding. We don’t do the funding bit – we don’t do the actuarial.

“The only potential conflicts of interest issue is that we do fiduciary and we do advisory, but we say to people ‘choose us for one or the other’.”

Cardano can certainly back up its claim to be doing things differently. It describes itself as arguably unique in publishing its investment performance data on its website, which it calculates as delivering improvements in funding ratios that are 25 to 30 per cent better than the market.

Cardano’s partnership with Monty Python legend Terry Jones in a feature-length documentary film called Boom Bust Boom also sets it apart from others in the sector. Now available on Netflix, the film looks at the way human nature drives the economy from crisis to crisis.

Understanding and mitigating the risks inherent in investing is at the heart of the firm’s strategy. Rosenberg is a big fan of cautious but steady growth over an all-in approach to investing, based on the idea that the next crash is coming, even if nobody can predict exactly when.

Understanding and mitigating the risks inherent in investing is at the heart of the firm’s strategy. Rosenberg is a big fan of cautious but steady growth over an all-in approach to investing, based on the idea that the next crash is coming, even if nobody can predict exactly when.

“I like to use an avalanche metaphor to describe investment markets,” he says. “Every day there isn’t an avalanche, you feel safer and safer. But actually the opposite is true. Financial history is a story of moving from crisis to crisis with nice periods in the middle. We should see financial crises as regular occurrences that take the puff out of the system.

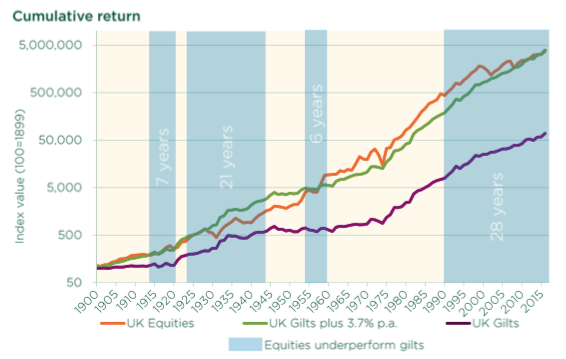

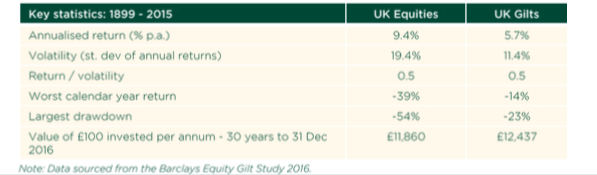

“It’s very hard to call the timing of them and it’s very hard to determine what will prick the bubble. We are nine years into a bull market and people think equities normally go up. But then they crash and when you look at the whole equities experience it’s not nearly as great as what it says on the tin.”

This, argues Rosenberg is as important for DC investment as it is for DB, and sets him against much of the established thinking in DC that maximum exposure to growth assets is needed in the growth phase. Rosenberg challenges the view that equities will outperform gilts over the long term, citing figures from the Barclays Equity Gilt Study that show £100 invested each year in the 30 years to December 2016 delivered £12,437 in gilts compared to £11,860 in UK equities.

The current binary equities v gilts and bonds model of investing is outdated, he argues, suggesting the DC market is ripe for some DB expertise, and hinting that a proposition could make it out of the laboratory in the next couple of years.

The current binary equities v gilts and bonds model of investing is outdated, he argues, suggesting the DC market is ripe for some DB expertise, and hinting that a proposition could make it out of the laboratory in the next couple of years.

Rosenberg and Redmayne are tight-lipped about what Cardano’s DC proposition will be, but they suggest a greater use of a broader range of assets – potentially up to 50 line items, including derivatives, and LDI techniques, will be part of the story.

Redmayne says: “One of the problems with DC is you are effectively a one-person DB plan. Using some of the best technology, we will be looking to achieve the DBfication of DC.”

Rosenberg adds: “For many people DC saving is made even more complicated because the DC pot is meant to produce an income in retirement. People are told about their fund performance, but if their cost of buying has gone up by 20 per cent, then they don’t know where they are.”

Rosenberg points to research carried out by Ralph Frank, Cardano’s head of DC, which analysed 29 default fund providers, representing 8 million members. This research found 38 per cent of defaults do not make it clear what the objective of the fund is, despite regulatory guidance for this to be unambiguous. None provide an explicit link between contributions and expected benefits at retirement, preventing savers from being able to accurately understand what level of retirement benefit is likely based on how much they are paying in. And almost two thirds have no clear performance objective, meaning savers are unable to identify whether a proposition is on track to reach its objectives.

Redmayne is critical of DB pension consultants that have made a virtue out of reducing employer contributions, only to see liabilities get worse. He says: “We are beginning to see that sponsors have spent a lot of time worrying about deficit and not enough time talking about risk. Consultants have defined success as keeping contributions low – ‘this means we’ve done a good job for you’. And a decade on the sponsors are saying to these consultants ‘well I have paid you a lot of money to advise me on this, but a decade later the problem is that four times bigger than it was’.

Rosenberg accuses some parts of the market of ‘mindless derisking’.

“Some are simply selling growth assets and buying gilts, and doing that in a fairly mindless mechanistic way is not a good idea. We are trying to spend a lot of time explaining the difference between risk management and returns management. It’s not as simple as to say that you have got one lever, equities versus gilts. That does not does not acknowledge diversification or derivatives.”

Talking to Cardano and Lincoln it is clear they spend a lot of time looking at different economic scenarios. So with gilt levels currently offering negative returns after inflation, are the markets effectively telling us that the economy is doomed? What do they think we should make of the current set of market indicators?

Rosenberg says: “We have had a nine year bull market and it is very hard to be bullish about equities right now.

“We don’t feel particularly worried about anything over the next 12 months. You have got synchronised growth – the US is growing, emerging markets are growing. But over the longer term we have got huge problems with debt, with ways inflation might manifest itself, causing money to be sucked out the system when interest rates could be pushed up to deal with inflation. So we could see everything falling together, bond prices, equities and property. It could be inflation that is the stimulus, it could be a debt problem in China, it could be a political crisis.

“You simply cannot predict what it is that could cause withdrawal of liquidity from markets. And all of this inflation in asset prices could be reversed. So we have to think through that.

“And if it doesn’t happen then okay. Do you feel sad if about spending your insurance premium if your house does not burn down?”

For Rosenberg it would be reckless not to plan for the worst – and that means looking to Japan.

“One of the scenarios we look at is that we could end up with a Japanese style situation in Europe. So you might think it’s silly to buy gilts with negative yields, but one of the scenarios is a possible Japanese scenario, which means gilts would be a fantastic asset class for the next decade. And in Japan, Japanese government bonds have outperformed Japanese equities for 50 or 60 years. If you use derivatives you can be much more flexible in how you can target that.”

Biography: Kerrin Rosenberg CEO, Cardano UK

Rosenberg founded and leads Cardano’s UK team and has overall responsibility for the UK business. Before setting up Cardano in the UK, he spent 15 years as an investment adviser at Aon Hewitt. He graduated from the University of Manchester with a degree in Economics, and qualified as an actuary in 1995.

Biography: Darren Redmayne CEO, Lincoln Pensions

Redmayne trained as a chartered accountant with the insolvency team at Deloitte. He joined Close Brothers in its corporate finance (M&A) division in 1998. After a secondment to the Pensions Regulator in 2006, he went on to found Close Brothers’ pensions advisory business before leaving to create London Pensions in 2008.